MOVING →

→ BEYOND

MAPS →

The Arrow shows leaders where their priorities should be. Will they act?

BY LEAH BINKOVITZ

Mapping almost anything in Houston, you end up with the same map, with a shape so persistent, so apparent, it's been given a name: The Arrow. How did the city take this shape? How has it held it? And how can we make Houston whole? This four-part series sets out to answer these questions. This is part four. Read part one, part two, and part three.

Preservation has proved a sometimes perilous path, raising the question of what is being preserved — places or a community — and for whom — residents, many who have been displaced, or tourists.

While not necessarily a matter of either-or, efforts to protect and preserve cannot escape these tensions. This is true for Freedmen’s Town, as well.

Episodes like the relocation of Jack Yates’ home to the downtown Sam Houston Park speak to the often heartbreaking compromises that have been made as the neighborhood has fought for control of its future and the resources to preserve its past. Today, there are ongoing efforts from groups like the Rutherford B. H. Yates Museum and the Freedmen’s Town Association and others, some aimed at providing for the neighborhood’s kids, some at buying and restoring historic housing, others at creating cultural tourism.

Blacklock-Sloan can remember one of her earliest visits to Freedmen’s Town. Growing up in Fifth Ward, she says she was amazed at what she saw — the wealth of old buildings and the history and people behind them. “These people are our heroes,” says Blacklock-Sloan, who has worked as the research director for the Yates Museum for two decades, “and I didn’t learn about any of them.”

When Pastor Pervis Hall was looking for a place to start his church, Freedmen’s Town was not initially on his map. But after attending a lecture at the Gregory School and walking out to see a for sale sign across the street, he reconsidered. That sparked a learning process for the Sunnyside-raised Houstonian, who knew little of this community’s history. He found himself in a meeting with many of the neighborhood’s longtime activists, including Gladys House-El, Lenwood Johnson and Catherine Roberts, who were organizing then to save the brick streets. “It’s kind of how we introduced ourselves to the community, by joining that fight,” Hall says.

The struggle is ongoing, including for House-El, whose latest effort to honor community elders with new street signs ran into pushback from the city about the size of them.

“So much has been stolen,” Hall says, “and there have been promises made.” The fight is particularly frustrating for him when he considers how much the community has had to do on its own over the years, including hauling dirt from Prairie View just to shore up the initial settlement along Buffalo Bayou. “It speaks to the resilience of African Americans in the city of Houston and the resilience of how they kept their true center in the midst of so much attack,” he says.

Any sort of preservation work in Freedmen’s Town has to deal with decades of contention around who actually benefits, he says.

“There’s several dynamics at play,” he explains. “There is a major distrust for entities that seek to exploit and make a profit off of Freedmen’s Town, and so many residents in the area are very secretive about their own participation or their own stake in the history and heritage of Freedmen’s Town. Because in the past they’ve done that, and they’ve been exploited by doing so.”

The community Hall thought wasn’t there anymore when he first went looking at official numbers emerged in his interactions in the streets.

The story of Freedmen’s Town, both its past and present, then, shows what can sometimes be lost in maps. Though the Arrow appears time and time again, the truth is less shapely, marked by much less of the feeling of inevitability that comes from static representations of people in space. Rebecca Solnit writes about the trust we have in maps to tell us the truth as “the way we take them for reliable or even objective statements and meet their sins of omission with our own.”

As with history, whoever produces maps — and how — holds tremendous power. Queen’s University professor Katherine McKittrick has written about the particular failures to see the experiences and insights of Black communities as geographically meaningful, calling out the role of maps in validating one kind of knowledge while dismissing others. “Geography is not,” she writes, “secure and unwavering; we produce space, we produce its meanings, and we work very hard to make geography what it is.” This means that “who we see is tied up with where we see,” writes McKittrick.

So, while the Arrow presents a useful bit of visual shorthand, there is more to it than can be mapped by traditional means. On a map, Antioch Missionary Baptist Church sits like an island surrounded by downtown parking garages and skyscrapers, just east of I-45. But the map does not indicate that in the 1950s, the highway destroyed an entire swath of Freedmen’s Town, separating the church from its home.

There is street-level nuance that is hard to render as imaginary boundaries, like census tract lines, take on material meaning.

And then there are notable absences.

Blacklock-Sloan takes photographs around the Freedmen’s Town neighborhood whenever she can, never sure which structure will be gone next and replaced by towering houses and large apartment buildings and garages. “It’s just so disrespectful,” she says. She has researched and applied for historical markers across the neighborhood and city, reckoning always with the weight of the work, of what she can’t save. “At least the markers will tell the story of what was here.”

Even the present can disappear in maps. When Hall first started canvassing Freedmen’s Town, he quickly realized that the hesitation to participate in government-driven processes extended to the census. “That’s why they didn’t show up,” he says, of his initial look at demographics when he was considering where to locate his church. “They’re still not accurately represented.”

And then there are the alternative presents that could have been. When Middleton thinks about those spaces, for example, she sees what she calls “the ghosts of failed projects.”

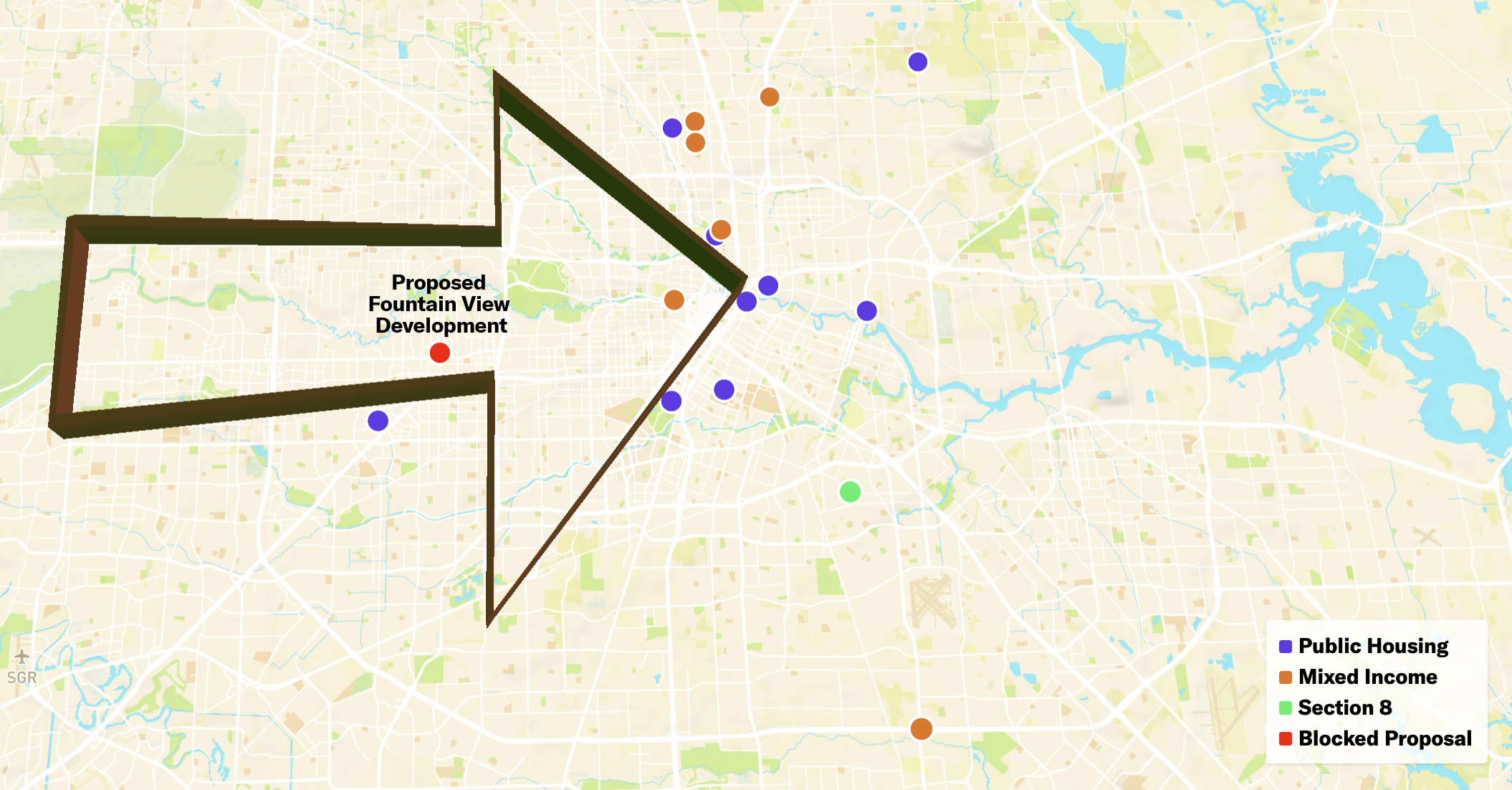

"There are these spirits of past developments or almost developments,” she says, recalling one shouted-down mixed-income housing development that would have been in the Arrow on Fountain View Drive. Residents said they feared lowered property values, among other unsubstantiated concerns. That’s who Mayor Sylvester Turner listened to when he effectively halted the project in a decision that would prompt the Department of Housing and Urban Development to investigate the city for a violation of the Civil Rights Act.

Missed — or stolen — opportunities for housing in so-called “high-opportunity neighborhoods” inside the Arrow represent a particularly detrimental loss. “Housing writ large gives people footholds in the community,” Middleton says. "It gives people a sense of belonging, and it has such an enormous impact on the ability to build and retain wealth,” including the many non-financial forms of wealth that often come bundled with affordable, safe housing. “I think that housing is the entry point to all of this,” she says. “It’s the entry point to creating the city that we want to live in and do live in.”

The Arrow might be specific to Houston, but the story is commonplace in U.S. cities. River Oaks, after all, drew its inspiration from Kansas City’s Country Club District. The Houston Informer — an African-American newspaper published by Clifton F. Richardson Sr. beginning in 1919 and using the printing press operated by Rutherford B. H. Yates in Freedmen’s Town — used to include its “platform” of priorities in each issue. Some were large, like “racial cooperation, teamwork, advancement, betterment and solidarity.” But many were specific: playgrounds for Black children, upgraded school facilities, legislation to end lynching, “good streets, better drainage and sanitary toilets” and more.

The list might read different today, but many of the aspirations remain, presenting opportunities for immediate redress: lead remediation, home weatherization, well-stocked grocery stores a walk away, robust shade and places for children to play.

The Arrow includes many so-called 'high-opportunity neighborhoods,' but few housing projects for people with lower incomes. Source: Houston Housing Authority

It would be a start. And the Arrow shows today’s leaders exactly where they should start. It shows them exactly where their priorities should be.

But stopping there would fail to address the systems that continue to create and then take advantage of inequity. Federal policies, like the mortgage interest deduction, which white households receive almost 80 percent of the value of, are complemented locally by practices like the city’s racist appraisal system. It isn’t enough to speak out against the ills concentrated outside the Arrow. The city needs also to acknowledge the ill-gotten gains inside it.

The Arrow makes it clear: The market is incapable of valuing lives equally.

Equity cannot be achieved with a government beholden to that market. There is a debt owed in Freedmen’s Town, and there is a debt owed outside the Arrow, too. Each mayoral administration has had the opportunity to do more, but too often politics appeal to the very philanthropic whims driving some of the city’s inequities. A donation here and there. A public-private partnership. A newly formed TIRZ or a special designation to help with fundraising. Corporate benevolence where there should be meaningful reparations.

Houston, we are reassured after deadly climate disasters, is “open for business.” But the vision shouldn’t be a uniform landscape of spaces modeled on the same old processes of extraction, dependent on favors and intent on accumulation.

“You look at the Arrow,” Middleton says, “and the Arrow tells a story of our priorities.”