Up and down

→ on

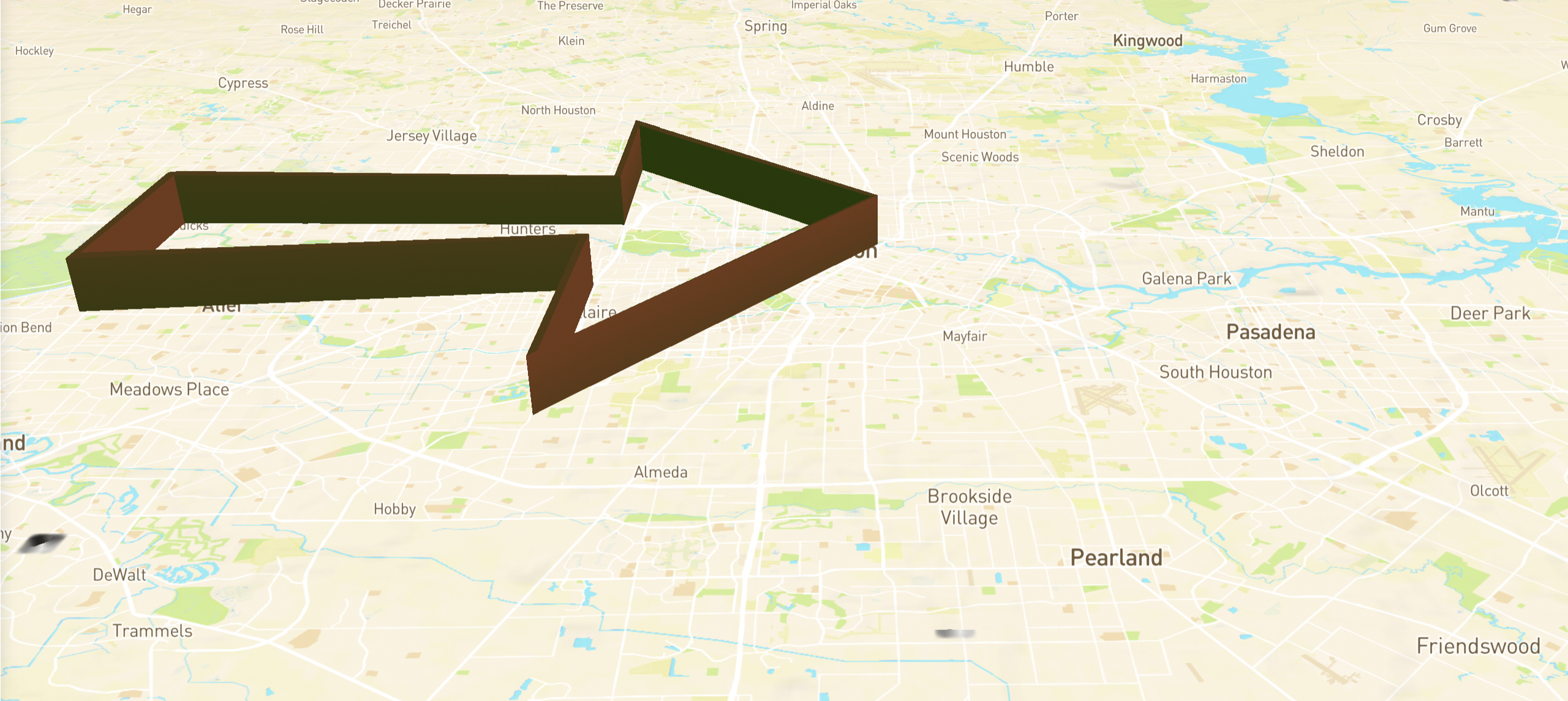

Richmond Avenue →

A straight line that reveals where Houston’s priorities begin and end

By Leah Binkovitz

Maps by Evan O'Neil

In her early years in Houston, Zoe Middleton’s commute would take her east toward downtown along Richmond Avenue.

That drive presented some of the many sides of the city, says Middleton, the Houston and Southeast Texas co-director for Texas Housers. “You see the whole state of buildings where people live,” she says, “these weird glass high-rises to single-family homes to multifamily that’s in need of a lot of attention and repair, and you see the difference in amenities.”

You see Houston, in short.

It’s a corridor of change. Near the Beltway, a single strip mall might feature Salvadoran, Cuban and Colombian restaurants with a Guatemalan bakery, an event venue, beauty supply shop and Pizza Hut.

The street also serves luxury car dealerships, members-only big box retail, and, closer to downtown, shimmering office towers in Greenway Plaza, mixed-use buildings like Kirby Grove with their own parks attached in Upper Kirby and bars, restaurants, grocery stores, art galleries and museums in gentrifying Montrose.

Before it changes names and becomes Wheeler Avenue in what used to be Third Ward, Richmond forms the rough southern boundary of a stubborn shape that most map-minded Houstonians have come to know by heart.