This is, in part, how the Arrow took shape. It’s how, in part, the Arrow is holding its shape. The Hoggs’ Memorial Park continues to get richer. A 2015 City Council-approved master plan led to an ongoing $205 million redevelopment, including a massive land bridge spanning Memorial Drive that Save Buffalo Bayou’s Susan Chadwick describes as a “seventy-million-dollar vanity project.”

Other seemingly neutral tools continue to funnel more wealth to wealth. Tax increment reinvestment zones exist across the city and are intended to support redevelopment in “areas that would otherwise not attract sufficient market development in a timely manner,” according to the city. These TIRZs are not intended to become permanent, but meant to aid areas that “constitute an economic or social liability” as a “menace to the public health, safety, morals, or welfare in its present condition.”

Some, though, have existed for a generation. The Uptown TIRZ even annexed a part of Memorial Park so it could help fund the improvements that will increase the value of the properties whose taxes are then skimmed into the TIRZ for more improvements.

Shelton, whose book details the way that economic and political power has wielded outsize influence in the shape of Houston, says, “There are TIRZs in all sorts of neighborhoods in Houston. The reason why downtown, Uptown and Midtown do more is because they have more real estate and more investment,” contributing to a cycle of accumulation. “Those are the neighborhoods that got investment and those are the neighborhoods that had political weight,” he explains.

And those are the neighborhoods that give the Arrow its shape. There is, however, more than one story contained in the Arrow. And more than one community has roots here. In the very point of the Arrow, the grid shifts and the streets narrow. Worn tracks from a long-ago streetcar are exposed between red bricks that have become a symbol of one community’s fight not only for recognition, but restitution.

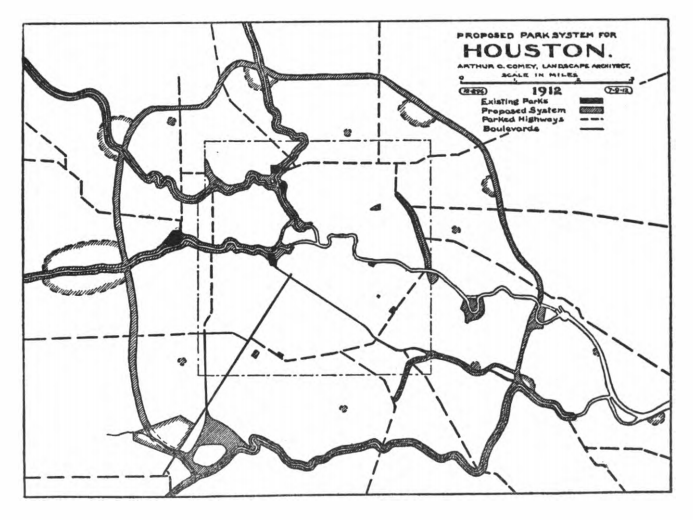

Screenshots from "River Oaks Scrapbook," available at the Houston Metropolitan Research Center and from "Houston: Tentative Plan for its Development" by Arthur Coleman Comey