Transportation can connect us. And it can isolate us. I've lived both.

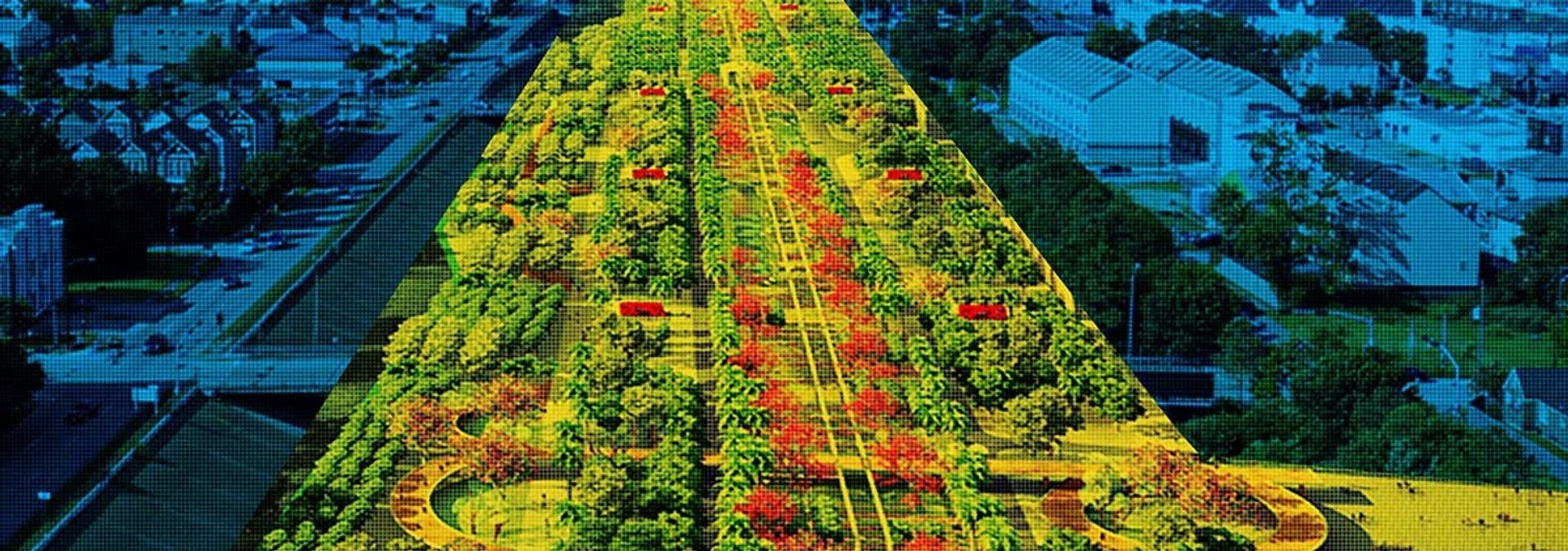

Shedding the metal-and-glass layers of a car has allowed me to feel more connected to the city around me. Illustration: Evan O'Neil.

In the rural Texas Panhandle, highways stretch for miles, flanked by high plains and unobstructed horizons. Long drives in your own car or truck are the default way of life, as there are essentially no other ways to get around. Growing up in this area provided me with little knowledge of public transportation, and I never imagined there would be a time in my life when I would not have, and want, a car.

When I left the Panhandle to attend the University of Houston, I was mesmerized by the massive city’s massive freeways. The intertwining concrete pillars stretched toward the sky as I idled next to them in my small Saturn Ion.

It didn’t occur to me to think about what was here before. What homes, businesses, even prairies were deemed necessary casualties?

I mostly avoided the construction that would eventually produce one of the widest freeways in the world, the Katy Freeway. Even if I had known about it then, I probably would have thought that the project was a good idea. When you’ve only ever been exposed to car culture, it makes sense to build infrastructure to move as many cars as possible.

Then I graduated and moved to New York City.

A few trips there as a tourist before I had moved had given me a romanticized version of the subway. I looked forward to giving up my car, daydreaming about sitting in quiet, uncrowded cars with my nose buried in a book.

My daydreams gave way to reality, though, because the subway could be an overcrowded, noisy space, and my nose was more likely to be buried in a stranger’s armpit. When that was true, though, or when I decided I didn’t want to pay the fare, I had options. I could just as easily use my feet. The walkable streets of Manhattan allowed me to explore the city in an intimate, adventurous way. Some days, I walked the entire length of the island, contemplating the history of each neighborhood I encountered.

In Texas, I’d never been able to get very far like that. My brother, a member of the local police force, jokes that walking in the Panhandle could get you reported for “suspicious activity.”

In New York City, I began to realize all the places my feet could take me. Shedding the metal-and-glass layers of a car allowed me to feel more connected to the city around me. Settling into my routine on the subway, I began to recognize familiar faces. I began to be recognized. I was becoming a part of something bigger than myself and discovering something I didn’t even know I had been missing.

Then I moved back to Texas.

I’d been thinking that it would be easy to transition back. I’d lived here for four years before, after all, and I enjoyed a network of grad school alums who helped me find a job and a place to live. But attempting to navigate Houston those first few weeks without a car left me feeling the most trapped and vulnerable that I had ever felt in my life. Houston is not a city designed with the pedestrian in mind. Really, it is hostile to pedestrians. I wanted desperately to explore, but it was clear the streets were not for me.

Shortly after, I felt I had to purchase a car. My office was seven miles away from my garage apartment on the east side. The slog of rush hour twice a day every day had me questioning how long I could make it here. Taking the bus would have added an hour and a half to my commute. People tell me I must be so happy living in Texas now, since the cost of living is much cheaper here. But the burden of a monthly car payment, insurance, gas and all the maintenance required to keep myself safe in your car goes well beyond the $120 I spent on transportation in New York City each month.

What I found there, I was losing in Houston. I enjoy living in cities, because I want to have regular contact with strangers. I want to know and learn from people who are not exactly like me. Being trapped inside a car trapped in traffic left me feeling detached, isolated from the city, not a part of it.

This is one of three essays written in response to the Texas Department of Transportation's proposed project to expand and reroute Interstate 45 through Houston. Read the others here and here.

One night, stuck in my apartment, I was browsing Twitter. I came across a hashtag that took me to a YouTube page for the Kinder Institute for Urban Research at Rice University, where a talk by Jeff Speck was posted, “What the proposed I-45 expansion means for Houston.” I’d never heard of him, and I’d never heard of the proposed expansion, but I was intrigued and watched the whole thing.

For months, I’d been struggling to resolve the anxiety and frustration I’d been feeling about getting around in Houston. I did not need Speck to tell me that driving is the least sustainable thing we do, or highway building is bad for cities. But as he spoke, the concrete pillars of the freeway system that had once mesmerized me now seemed deliberately divisive barriers, ripping apart neighborhoods and revealing which people our department of transportation considers expendable.

Infrastructure focused on moving cars only, and not all the ways people move, is obviously inefficient. And it is killing us. Children are expected to live shorter lives than their parents, because we have prioritized driving over walking and biking. As freeways move closer and closer to schools, children are the victims of degraded air quality, leading to serious health issues.

For decades, Houstonians have been asking for public transportation. Nearly 60 percent of respondents to the most recent Kinder Houston Area Survey said it was "very important" to the city's future — only to be offered freeway expansion after freeway expansion. Access to reliable, dependable buses and trains that take us where we need to go, safe, wide sidewalks and bike lanes for all ages and abilities should be a given in a city, but Houston has prioritized cars to the exclusion of almost all other options.

That doesn’t mean it can’t. That doesn’t mean it won’t. At the end of Speck’s talk, someone in the audience asked, “What can we do?”

He said, “Organize.”

Imagine spending billions of dollars building all options for all Houstonians, instead of continuing to widen, expand and double down on the one that is burdening us instead with costs, stress, lost time and unhealthy air. Imagine a network of high-comfort bike lanes connecting our bayous to our sidewalks to our houses to our transit centers to our parks to our offices. Imagine prioritizing people, not cars. You might discover what you thought you’d never find in Houston has been there all along: your community.

Alejandro completed her master’s in vocal performance at the University of Houston before working as a project manager in advertising. In 2018, she joined the team at the Memorial Park Conservancy.

STAY UP TO DATE

The quality of our newsletter is considered satisfactory and poses little or no risk.

SUBSCRIBE